Note: Our site links to archery and bowhunting products sold by outside vendors, and we may earn a small commission if you purchase an item after clicking one of these links. Learn more about our affiliate program.

Credit to www.bowhunter-ed.com for the awesome graphic

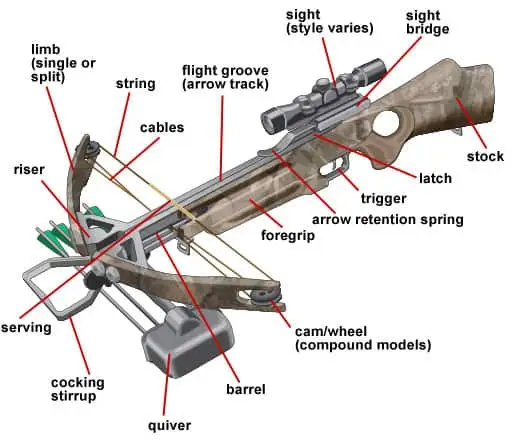

Before diving into the world of bowhunting and archery, its important to learn the parts of a crossbow. We’ve created a quick guide to help you learn the ropes.

Anatomy of a Crossbow

A crossbow is basically a vertical bow mounted horizontally on a frame. The frame contains mechanisms that hold the bowstring, which can then be released to fire the crossbow. It’s also important to know that the projectiles normally fired from crossbows are referred to as bolts, though you may sometimes see them called arrows as with regular bows.

Since it’s a bit more complex than a vertical bow, understanding the anatomy of a crossbow can help you use it more effectively. Here are the main parts you should know.

Limbs

Limbs are arguably what make a crossbow, or any other kind of bow, an effective weapon. Traditionally they were made of flexible wood. These days limbs can be made of many different materials including wood, aluminum and carbon fiber. They branch out from the center of the crossbow symmetrically, and each limb attaches to one end of the bowstring. The string can be pulled back, and the limbs bend instead of breaking. Then, when you let go, the limbs spring forward with all their stored energy, launching the arrow or bolt at high speeds.

Bowstring and Serving

The bowstring attaches to the limbs at either end. If you pull the string back, it pulls the limbs back, which then act like springs. When you release the string, it will fly forward. As a result, if you put a bolt in front of the string, it will transfer all the kinetic energy into the bolt and shoot it at hundred of meters per second. To do all this effectively, it must be made of lightweight yet durable, flexible material. This usually means natural fibers like linen or animal sinew or synthetic fibers like kevlar or dacron.

Crossbow strings also feature something called a serving. This is often some kind of synthetic material coated with resin that’s wrapped around the bowstring in the area where it’s drawn and held. When you cock a crossbow, mechanisms hold the bowstring in the drawn position until you fire. These can wear down the string, so the serving protects it.

Risers

The risers connect the limbs to the rest of the crossbow. Since there must be space between the limbs for the bolt to pass through, a crossbow must feature two risers, one for each limb. These are usually made of strong machined aluminum that can withstand the intense amount of pressure put on the limbs.

Rail

The rail is also known as the track or barrel, and like the barrel of a firearm, it is the long part of the weapon where the projectile, in this case the bolt, travels while it picks up speed. Specifically, it’s the area between the limbs and the latch that holds the pulled-back, cocked string. The bolt rests here until it’s fired. Modern crossbow rails feature something called a flight groove as well that keeps the bolt straight as it leaves the rail.

Stock

The stock does not actually serve any functional purpose on the crossbow. Rather, it’s the part that makes the weapon possible to hold for a human being and connects all the necessary mechanisms together like the rail, latch and trigger. Just like with a firearm, they have large butts that you can rest against your shoulder and thinner foregrips where you steady the weapon. Their shapes can vary greatly for ergonomic purposes and easier holding. They can be made of just about anything, usually wood, but sometimes molded plastic or some other synthetic material.

Foregrip

When you’re holding a crossbow, the butt of the stock will press into the shoulder of your trigger hand. Your other hand will hold the crossbow beneath the rail by gripping something called the foregrip. Of course, this is necessary to properly aim and steady the weapon, which would otherwise shoot erratically. Modern crossbow foregrips are sometimes collapsible or removable for added convenience.

Cam Systems

Compound crossbows increase power while decreasing draw weight and limb length by employing pulley systems called cams. These are basically just wheels that the bowstring threads through. The cams, which can be round or oval shaped, then store kinetic energy along with the bowstring. Cam systems also have cables separate from the bowstring that are necessary to keep the cams synced and transferring energy.

Trigger

Most people are familiar with triggers, even if it’s just from a squirtgun. This is what you pull to shoot the weapon. In the case of crossbows, triggers release the latch and let the string and bolt fly forward. Although they all serve the same basic functions, different crossbows position their triggers differently, some directly beneath the latch and others in front of it.

Latch

On a regular bow, you have to hold the bowstring back with your own strength and then release it. Crossbows make it easier by holding the string back with a mechanism called the latch. When you pull the trigger, the latch disengages and lets the string fly forward.

Arrow Retention Spring

Almost any modern crossbow will feature an arrow retention spring. This is a metal bar that forces the bolt into the flight groove. It’s necessary because, without it, if you turn the crossbow even slightly away from level, the bolt can fall out of the rail or at least become slightly off center. Therefore, the arrow retention spring is especially useful for hunters since it lets you cock a bolt but then still move around with the crossbow. Retention springs are usually made of metal or plastic.

Cocking Stirrup

Crossbows are much more powerful than regular bows and therefore have a much higher draw weight. This is the amount of force you need to pull the bowstring back. As a result, you need a lot more leverage to draw a crossbow. The solution is a cocking stirrup, a kind of loop extending from the rail of the crossbow that you can stick your foot into. While holding the weapon down with your foot, you can pull the string upward using the full strength of your body.

Anatomy of a Crossbow Bolt

Credit to www.fearlesstactician.com

Now that you know the anatomy of a crossbow, you also want to know the anatomy of its projectile, the crossbow bolt. Believe it or not, bolts actually consist of quite a few different parts.

Shaft

The shaft is the long, main part of the bolt that connects all the other parts together. Traditionally, they were made of wood, but modern bolt shafts are made from materials that maximize both light weight and strength like aluminum and carbon fiber.

The flexibility and weight of the shaft are very important to a bolt. The flexibility is measured in spine. A bolt with more spine is more resistant to bending. Meanwhile, the weight is measured in grains. A grain is, at least in modern times, an archery-specific unit of measurement. It’s equivalent to about 65 milligrams.

You may also see bolts measured in grains per inch, or GPI, which gives you the weight proportional to the bolt’s length. This is useful for comparing bolts of different lengths. The total weight can then be determined by multiplying the GPI by the length of the bolt.

Nock

The nock is what connects the bolt to the bowstring. They take the brunt of the force from the string and protect the more delicate shaft. Because of this, they’re normally easily replaceable.

On a regular arrow, the nock must grip the string, but this is unnecessary on a crossbow bolt because the shaft rests on the rail. The bowstring merely has to push against the back of the bolt. As a result, many crossbow nocks are simply flat discs. Other forms try to take more advantage of the string’s power and help the bolt fly straight. Common nock types include:

Flat

Half-moon

Capture (a deep u-shape similar to that of an arrow nock)

Multi-grooved

Fletching

You’ve probably seen the feather-like wings at the rear of an arrow or bolt just before the nock. They’re one of the most iconic symbols of archery after all. These are the fletches, and they’re necessary to stable the bolt in flight. Without them, a bolt could veer off course or pitch to the left or right. Fletches often cause the shaft of the bolt to spin which dramatically improves accuracy.

Arrow fletching used to be made from real feathers, but that’s rarely the case nowadays. Arrows for traditional bows like recurve and longbows may still use fake feathers made from synthetic materials, but crossbow bolts travel so fast that solid plastic fins are necessary.

Point

Also called the head, bolt points are the sharp or pointed front ends of bolts designed to penetrate targets, whether a foam box or a thousand-pound moose. Although almost always made from strong metal like stainless steel, bolt points come in a variety of forms. For example, field tips are simple conical points used for target shooting. Meanwhile, hunters use broadheads, which have flared metal blades that cut through flesh. There can be two, three or four blades, and they can be fixed or, in the case of mechanical broadheads, retractable. The blades only flare out when the broadhead strikes its target.

Common Accessories

The anatomy of a crossbow can get a little more complicated when we consider the many accessories necessary to use it properly. In fact, many of these are so important that they’re almost always included by crossbow manufacturers.

Sights and Scopes

To aim a crossbow, you need some kind of sight. Many crossbows come with open sights, which feature a pair of markers, one in front and one in back, that must be aligned to aim the weapon. The front sight is often a single point that must be aligned within a notch or circle that forms the rear sight. When aligned, the crossbow is accurately aimed at its target.

Optical scopes use light, mirrors and other advanced optics to aim a crossbow. Sometimes these come with the model, but more often, archers buy these scopes as separate accessories.

Unlike firearm sights, crossbow sights and scopes must be tuned for a range of distances because bolts begin to drop as they travel long distances. This is usually solved by having multiple pins or cross hairs marked for different distances. Once you zero in the sight or scope for the shortest distance, it will be accurate at the longer distances too, marked by lower pins or cross hairs.

Trigger Safeties

A trigger safety is an important part of any modern crossbow. These mechanisms don’t let you fire the weapon without disengaging them. This keeps you from accidentally shooting the crossbow while you’re moving around and hurting yourself or another archer.

Any professional crossbows on the market today should come with at least a manual safety. In this case, you engage the safety after you cock the crossbow. Then, when you’re in position to shoot, you disengage it. Automatic safeties are a new option out there that add an extra layer of safety. These engage automatically when the latch catches the string so you can’t forget.

Quivers

You have to carry your bolts around somehow. You’ve probably seen the classical Robin Hood quivers that sling over your back or around your waist, but while you can certainly get one of these if you want, you have other options too. Specifically, you can get a mounted quiver attached to your crossbow. These hold several bolts using easy-release mechanisms. Not only does this make your weapon easy to reload, but it cuts down the amount of things you need to carry around with you.

Slings

It can be hard to hike through thick woods with a loaded crossbow in your hands. The solution is a sling that goes over your shoulders and holds the crossbow in an easily accessible position behind your back.

Cranks and Drawing Aids

Like we mentioned before, crossbows are powerful and therefore take a lot of force to draw. Many systems exist to overcome this. Most commonly, you can purchase cranks that attach to the stock of the crossbow. You turn the crank, and it pulls back the bowstring. Besides cranks, you can also get simple drawing aids, usually ropes that attach to the string and allow you to pull it up with more leverage.